There’s something telling about a series that, when I had first decided to episodically blog it in the beginning of the winter season, started off interesting and full of intrigue and potential, but fell flat enough to lose said blogging interest as soon as the sixth episode. For a person who had (not so) recently closed the doors on his main Warcraft blog to focus primarily on this anime blog, the disappointment that would lead to such inactivity leaves a very bad aftertaste in this author’s career as an aniblogger.

That said, despite the fact that Fractale failed to build upon the foundation that it laid out at the start, that very foundation still remains at the end, challenging those to look at what was given and improve upon it themselves. In essence, the series’ severe imperfections serve as an excellent teaching tool for proper storytelling at the expense of the series itself.

Starting with the very premise of the show itself, Fractale seeks to show the audience a world where humans depend on the titular system, living off the sustenance Fractale provides at the cost of segregation and independence of individuals from each other, bringing the family unit to obselesence. The story introduces Clain, a boy who questions the nature of Fractale, and finds his home and family in the characters he meets, particularly Phryne, Nessa, and the Lost Millennium resistance group.

By pitting him in an awe-inspiring scenic world reminiscent of romantic Ireland, Fractale sets the stage for a journey into adolescence, and the moral choice between coerced provision and fulfillment through cooperation and sacrifice. However, the main character never gets to make this decision for himself. Clain spends the entire series confused by the greyness of the situation presented to him: the extremist Lost Millennium rebellion struggling against the tyrannical brainwashing of the Church of Fractale. Neither side is good, and the indecision from Clain’s limited point of view stalls the progression of the overall conflict against Fractale. The viewer expects that Fractale is the worse of the two evils, and its downfall would fit Clain’s character change more suitably; however, Clain takes forever to realize this, and when he does, the audience is tired of his beating around the bush, and the impact of his revelation is severely lessened to the point of inconsequence.

And that’s only the internal conflict that the Clain faces throughout the story. The primary character development comes from his external relationship with Nessa and Phryne, the keys to the slowly ailing Fractale system. The development of this particular character triangle initially attempts to run concurrent to the primary conflict between Lost Millennium and Fractale for additional effect. However, the triangle itself develops too slowly, resolves too soon, and becomes utterly incomprehensible at the end.

Structurally, a horrendously weak second act paved the way for a very tired conclusion, despite a relatively well-paced pair of final episodes. Series writer Hiroki Azuma shows familiarity with structure and theme as is his forte as a literary critic, but his lack of experience with actual story writing shows. He makes many mistakes with regards to telling instead of showing, and his characters are too factional, and don’t relate to each other at all. They all preach different sides of the argument without actually attacking each other in any severe way. Character deaths in this series are few and wasted. Side character appearances provide opportunity for development of primary characters, but serve to further their own agenda despite their limited screen time, resulting in wasted episodes.

The show is not without its redeeming features. The pseudo-scientific open setting is like that of a futuristic Ireland, and its art is vast and breathtaking. The music is inspirational at times, though others may portray moods that may or may not have been intentional, considering the saturation of needlessly awkward moments between characters, primarily involving Clain. The ending theme is a rendition of Down by the Sally Gardens, a haunting melody sung by Hitomi Azuma, varying between English and Japanese. The Japanese lyrics are awkwardly placed with the melody, due to the multisyllabic nature of the language in relation to English. It results in a sort of rhythmic dissonance that comes off as awkward. Coincidentally, the inferior Japanese version is used in the same episodes that span the lacklustre second act, switching back to English when the show picks up again.

Voice acting was solid overall, with notable performances from Shintaro Asanuma and Kana Hanazawa, who play the Sunda and Nessa, respectively. Sunda is a stern leader who does not mince words. Asanuma plays off his prior experience as the energetically verbose watashi from the Tatami Galaxy, and makes every syllable count. His command of the language is persuasive, that despite the poorly aligned morality of his character and affiliates, he is a strong leader, and preaches his convictions better than the rest of the cast, even if they do come off as preachy.

Nessa is a digital doppel, naïve and childlike. Despite lacking much depth in the screenplay, Kana Hanazawa reduces the flatness of Nessa’s character with lively dialogue, playful intonation, and the right mix of endearment (to Clain and Phryne) and annoyance (to everyone else in Lost Millennium, save for the children). Kana’s character gets little opportunity to react in extremities, but she brings out different dimensions through Nessa’s non-doppel human form, who appears in episodes 4 and 8. This faux-Nessa is the polar opposite of the cheerful energetic original that we associate with, and Kana really brings out that distinction. In the few brief moments where real-Nessa shows variance in emotions, particularly in reaction to developments surrounding Clain and Phryne, Kana does an acceptable job without being too over-the-top, as she is known to do with some of her her one-dimensionally written moe characters. Nessa barely escapes this, which is a feat in itself, given the dialogue that was provided.

The need to examine the motivations behind producing such a show as Fractale cannot be helped; even Scamp’s MAL analysis focuses solely on it as the main criticism behind the show’s mediocrity. I argue that the motivation of many, particularly due to the hubris of director Yutaka Yamamoto. His assertion that Fractale would save the anime industry stirred ire in a subsection of the fanbase. Whether it was interpreted as hubris or as a direct slam at the community, there were many reasons to oppose the show, invoking a stubborn bias against the show from the get-go.

I admit to turning a blind eye to Yamakan’s outspokenness at all, giving Fractale the benefit of the doubt. I don’t regret it, because even without the bias against Yamakan, Fractale still turned out as a disappointment, and the resulting humiliation of the show’s director after failing to live up to his words is a sad sight; those with such biases revel in it. Regardless, schadenfreude does nothing to help the industry, and I can only hope that Yamamoto bounces back and tries to contribute in a meaningful, yet still outspoken way.

Fractale was a learning tool for both those who wish to further understand the nuances of story development and structure, as well as the individuals who worked on the show. I expect better in the future, and hope that the mistakes made in Fractale will not be repeated.

Score: 5/10 (Average)

Great review 🙂 I reckon Fractale was the biggest disappointment to everyone. noitaminA + Great setting = Unlimited potential. But somehow, it manages to screw everything up.

A mention of Enri’s incessant “ecchi, ecchi, ecchi” cries and the inane ecchi jokes could’ve been brought to light in the review, in my personal opinion.

Oh, and use screenshots. It breaks the monotony of reading.

Lovely post, overall. Me subscribe.

I considered adding in particular examples of such awkward moments as you have mentioned, particularly mentioning Clain’s thong in episode 5 as the penultimate example. However, despite that one ineffective running gag and somewhat run-of-the-mill voice acting, I liked Enri’s character, particularly her perspective and dilemma of being somewhat immature, yet thrust into a war she is clearly unable to handle emotionally. Again, wasted potential, but she and Sunda were my favourites in the cast, if I had to pick at all.

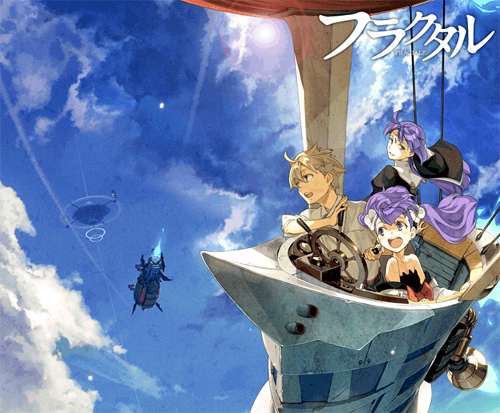

You know, it just occurred to me. If the original character designs had been maintained in the actual drawings, it would be more obvious from the beginning that Phryne, Nessa, and Moeran are all related because of the same hair color. Even Sunda and Enri originally had identical hair colors, lending to the idea of a family trait.

I can’t help but feel that such last-minute changes were made out of hesitation, because it clearly set up for a very hesitated production when the series finally aired. I suppose my use of the original promotional material lends to that whole theme of wasted potential that I repeatedly emphasized in nearly every aspect of the show.